John Hall‘s alliterative epithet for what he calls “live utterance” seems like an appropriate appropriation for the title of this post, which is not so much a review of the monumental achievement of Hall’s Essays in Performance Writing. Poetics and Poetry Vols. 1 and 2 and of Tony Lopez‘ The Text Festivals: Language Art and Material Poetry, as it is a way of thinking with their relation and co-incidence, published within weeks of each other. Handily for me, as I’m leading the first of three Archive of the Now workshops this week, in which I’ll be working with A-Level students to investigate

the blurring, sliding and abandonment to silence or physical gesture that live utterance allows, where the buck can be passed from code to code, always an alibi available, or a continuity to override the end of something being joined (Hall, 58, Vol. 1).

“The end of something being joined” might stand as a description of the current mainstream poetry of closure against which both performance writings and text art experiment. Hall’s and Lopez’s books follow on the heels of Geraldine Monk‘s CUSP: Recollections of Poetry in Transition, all three offering critically-attuned insider accounts – auto-ethnographies, really – of the diffuse, ex-centric British avant-garde. Monk’s is the broadest, being transgenerational, while Hall’s focuses through his involvement in the foundation of the Performance Writing course at Dartington to provide a wider statement and review of its manifestations in poetics beyond Dartington; Lopez, meanwhile, offers a vertical tranche of the Text Festival archives, provided primarily through thick description by participants, as well as his and Tony Trehy’s introductory overviews of text art and/or vispo.

Contested terminologies (Hall provides a glossary), interlocking communities, and readings in (what can feel like) a vacuum are common to both books: they go with the territory. While contextualising the field, Hall is predominantly committed to arguing for performance writing as a theory of itself, and hence for our attention as readers to its internal logics; to his formulations as contingent, attendant on a given text, rather than as transferable conclusions. These “implicated readings” as the second volume is subtitled, are not only implicated by Hall’s friendship with the writers whom he discusses, but proceed – as pedagogical and critical models – by implication.

This is most evident in “Reading J.H. Prynne‘s ‘Acquisition of Love’ and anticipating ‘Blue Slides at Rest.'” Originally given as a talk at Birkbeck, the reading by Hall asks the listener/reader to anticipate an implicated reading of Prynne’s later, and very different, poetics, by contrast and comparison. “What to do with this? It will not come to rest,” he concludes (209, Vol. II), an implication that could stand for the two-volume collection as a whole, as a vivid, mostly unedited collection of moments of reading and speaking. Throughout, Hall is concerned with and compelled by the destabilising effect of speaking and of listening on meaning, as charms against ossification, and the particular value of speaking/listening within the context of poetics because it is – and because it makes poetics unavoidably – a public language. “Public language is always either fully authorised or openly contests authority and its sites of authorisation” (72, Vol. II).

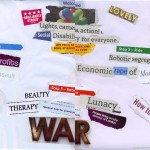

It’s this idea of experimentation producing a reflexively public poetics that inspired the Text Festival as well. As Lopez and Trehy, as well as Christian Bök (who is intervening in genetic code), Carol Watts (intervention: alphabet), Holly Pester (intervention: the archive) and Hester Reeve (HRH.the) (intervention: protest), detail, part of the motivation for making, performing, and curating text art is its critical engagement with “fully authorised” public languages in order to reclaim them for dissent. Reeve’s essay queries conventional attempts to contest public language, and suggests ways to renew them.

By 2003, the second Gulf War had broken out and what turned out to be one of Britain’s largest mass protests had taken place and been rendered ineffectual. What else could we do with our bodies in such circumstances? What was my body able to do, how could it count, what truth could it realise? I became struck by the powerful tactic of the slogan ‘Not in My Name’, which arose at the time and which allowed any one of us anywhere in the country to still make a stand, if only through a slogan (130).

Reeve places the intervention of the first Text Festival (2005) in the context of what Judith Butler calls the “frame of war,” the optic obscured by the very media and political infrastructure that produces it. It’s interesting to consider whether it is this frame of war – bringing with it both a sense of the ineffectuality of protest (which informs and draws on many of the experimental strategies of performance writing and text art, or oral and graphic culture jamming) and its necessity – is in some way a prompt for the current revisitation of the post-war British avant-garde.

Current political challenges to the kind of cultural spaces that made Dartington and the Text Festivals possible may not be directly related to a war economy or wartime surveillance, but they are a product of a militarised economy and surveillant system, and this is of concern to both projects. As Hall says “There is a difference between publicly available and publicly conspicuous: access and reach” (73, Vol.2). These publications – Hall’s book, like Monk’s, by Shearsman, and Lopez’ by University of Plymouth Press (who very generously provide a selection of full-colour plates) – are publicly available, and hope to make the work they detail publicly conspicuous, at a time when avenues for reach (if not access, given digital media) are narrowing. While neither of these books will be etched into a railway bridge, like Lawrence Weiner’s WATER MADE IT WET as described by Lopez in his Text Festivals introduction, they do take place/space in the public sphere.

In doing so, they walk/work the delicate balance involved in archiving the ephemeral without ossifying it, a challenge that all such archives or documentation face in defending experimental work from obscurity. Preserving liveness is an oxymoron, one of which Lopez and his contributors are aware. Watts, describing her artist’s book alphabetise, talks about the way “[w]hat began as a form of journal writing in 2004-05, copied into electronic form, became a series of transpositions, in which the handwritten itself at some point flick-flacks to become secondary to the recording of the printed word” (49). Even as it suggests the supervention of the archival – electronic, recording, printed – the sentence flick-flacks (a movement in gymnastics), an embodied performance that reinscribes the printed text as having bodily movement, the “alibi available” to the performative that Hall suggests.

“In what ways did the sound files resist being archived?” asks Pester, offering a tangential response with a selection of work by Carolyn Thompson, for whom “secrets within an archive are the only spaces fit for occupying” (113, 116). Philip Davenport reports, in both comparison and contra-distinction, on the deliberately elusive effervescence of Bob Cobbing’s work as poet and publisher, of an immediacy that sought to defy reification. “His emphasis was on giving permission, on imagining new routes” (57). Giving permission and imagining new routes is the work of both books: in each case, they offer pragmatic advice as well as conceptual frameworks. Trehy offers pointers on staging a festival, while Pester, Reeve and Robert Grenier give insights both into producing work, and participating as guests in a locale. A guidebook, a catalogue, a manifesto, an imagining: Lopez’ book is an archive constituting its own unpredictable future.

Hall’s book is a textbook by being its opposite; in no way prescriptive or exhaustive, offering no syllabi or lesson plans, it’s an exhilarating experience of the affective and processual inside of a pedagogy, one that makes space for the reader as both student and colleague. “The written is notionally not ephemeral, that is the point. But the acts themselves of reading and writing are live, and without those acts the written is no more than archived potential for renewed liveness” (48, Vol.1). This is a tremendously liberating way to think about the written, as always about to flick-flack, as well a wonderfully generous tribute to reading and readers, a generosity Hall’s own implicated readings enact.

Each book individually offers a rich engagement to the reader, with work known and unknown; indeed, redrawing the parameters of a textual artefact’s knowability. How many performances of this poem have you seen? How many readings have you made? Did you see it on the bridge? Together, they have a cumulative overwhelmingness of an intricate experimental poetics of almost infinite connective detail. That sense oscillates with a welcome open-endedness, a space for intervention. Or, how freeing to realise that “[t]he full stop has fragile authority once it has to leave the page” (Hall 58, Vol.1).